State of the Art Analysis¶

This chapter analyzes the systems set up in the appendices. The analysis examines their technical functionality and evaluates their complexity, features, and user-friendliness.

TrustedGRUB2 presents several compelling reasons for inclusion in this analysis. First, its source code is publicly available, offering a much deeper insight into its technical functionality compared to closed-source alternatives such as the Windows Bootloader. Second, GRUB, and by extension TrustedGRUB2, supports BIOS-based booting. While other open-source alternatives like systemd-boot and Clover also exist, they require UEFI-based booting. Lastly, TrustedGRUB2 supports measured boot processes, a feature that is rare among open-source bootloaders and the primary reason why alternatives like Syslinux were not considered.

QubesOS with the AEM extension is also well-suited for analysis for several reasons. The extension offers a highly configurable solution for detecting Evil Maid (EM) attacks, providing various options for boot media and flexible forms for secrets. In addition to its extensive configuration capabilities, the extension is open-source. While Windows BitLocker also supports a range of configurations, its closed-source nature makes it less suitable for an in-depth analysis. Finally, the comprehensive documentation of the AEM extension stands out as a major advantage. Beyond installation instructions, it includes detailed information about potential attack vectors and recommended countermeasures.

The combination of both solutions is logical, as they employ different approaches to establishing the Root of Trust for Measurement. TrustedGRUB2 utilizes a Static Root of Trust for Measurement (SRTM), while the AEM extension for QubesOS employs a Dynamic Root of Trust for Measurement (DRTM). Furthermore, they diverge in their methods for creating the initramfs. QubesOS leverages the dracut tool, whereas the Arch Linux system with TrustedGRUB2 uses mkinitcpio. Gaining an understanding of both approaches positively impacts the overall outcome, as it enables selecting the most suitable method. However, the criteria for comparison still need to be defined.

This analysis aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of existing solutions. Knowledge of available features serves as a guideline for designing a custom approach. Insights into the functionality of individual solutions can be utilized to evaluate the feasibility of a combined solution using existing components. If such an integration proves impractical, the understanding of the underlying technologies can form the foundation for developing a new solution.

TrustedGRUB2¶

Appendix B details the setup of an Arch Linux system with TrustedGRUB2. The following section provides an in-depth analysis of this system.

In general, TrustedGRUB2 can be characterized as outdated and poorly maintained.

The last commit to the TrustedGRUB2 repository (e656aaa) occurred on June 8,

2017. Since that time, 294 commits have been added to the upstream GRUB

repository (see Section Listing 3). The date of the last

commit, combined with the significant divergence from the upstream GRUB 2

codebase, suggests that the project has been abandoned.

Technical details¶

In a system using traditional GRUB, the chain of trust terminates after the Master Boot Record (MBR), as the MBR lacks support for the Trusted Platform Module (TPM). TrustedGRUB2, a fork of GRUB version 2.02, extends the chain of trust to include the operating

Fig. 8 Trusted GRUB 2 Chain¶

The final component measured by the firmware is the Master Boot Record (MBR). In a system using GRUB, the MBR loads the first sector of the GRUB kernel (diskboot.img) and then transfers control to it. To enable measurement of this loaded sector while keeping its size under 512 bytes, the CHS (Cylinder-Head-Sector) code was removed. PCR-08 is extended with the SHA-1 hash of diskboot.img, after which the boot process continues [2] (chap. 11) [42].

diskboot.img loads the remaining sectors of the GRUB kernel (core.img) and extends PCR-09. This kernel is capable of interpreting various file systems, and further measurements depend on the configuration file grub.cfg located on the hard drive [2] (chap. 11) [42].

The modular structure of GRUB allows for the loading of code at runtime. These so-called modules must, of course, also be measured. TrustedGRUB2 extends GRUB so that each module is measured into PCR-13 during the loading process.

All commands contained in the grub.cfg file are interpreted by a shell, which is also used in the command line accessible to users in the GRUB menu. With the extensions of TrustedGRUB2, every command executed from the shell is measured into PCR-11. The configuration file is located in the unencrypted boot partition, and its contents is shown in Fig. 9.

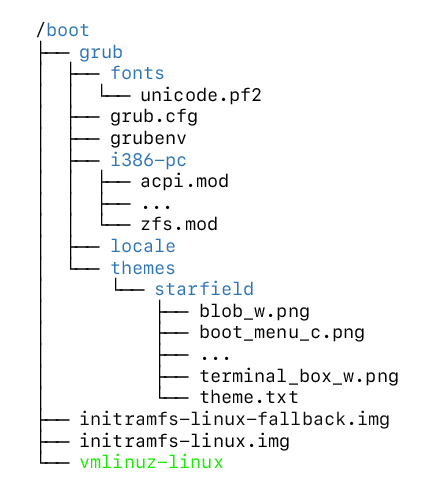

Fig. 9 Trusted GRUB 2 boot partition contents¶

With the loaded configuration file boot.cfg, GRUB is ready to load the

operating system kernel. To ensure that the kernel is also measured, the

commands linux and initrd were modified by TrustedGRUB. The linux

command loads a Linux kernel from the hard drive and passes all subsequent

parameters to it. The initrd command can only be executed after the

linux command and is responsible for loading the initramfs from the hard

drive [2] (chap. 16.3.37, chap. 16.3.33). Afterward, the kernel is started with

the initramfs, completing the process, and TrustedGRUB2 no longer retains

control over the system.

The image Fig. 9 displays the output of the tree command in the unencrypted boot directory. Most of the files in this directory are measured by TrustedGRUB2 and have already been discussed in detail.

The file grubenv, which has not been previously mentioned, is used by

the bootloader to retain information across reboots. The commands

load_env and save_env allow the GRUB environment to be loaded

from or saved to this file. To prevent this process from introducing a security

vulnerability, the loading of this file must either be disabled or the file must

be measured using the measure command provided by TrustedGRUB2

[2] (chap. 15.2) [42].

The locale directory in this system is empty, though it typically

contains information for the use of GRUB in various regions. If the environment

variable locale_dir is not set, internationalization is disabled,

rendering the files in this directory irrelevant. If internationalization is

desired, the measure command can be used to measure the locale files

for added security [2] (chap. 15.1.19).

The handling of theme files is similar to that of internationalization files.

They are not automatically measured by TrustedGRUB2. Consequently, their

integrity must be ensured using the measure command, as themes cannot

be entirely disabled. It is worth emphasizing that exploiting a security

vulnerability in GRUB would be necessary to inject unmeasured malicious code via

theme or locale files.

The technical architecture of the system has been comprehensively analyzed, detailing the data stored unencrypted on the disk, the programs that assume control of the system, and the specific contents recorded in the PCRs. The subsequent section transitions into a critical evaluation, beginning with an analysis of system complexity.

Complexity¶

A preliminary indicator of the complexity of a software feature can be the total lines of code it comprises. The modifications introduced by TrustedGRUB2 are clearly delineated in the source code with start and end markers. This allows the augmented code to be extracted using the command illustrated in Listing 4. The total lines of code added amount to 3,297, which can feasibly be reviewed within a single workday. The majority of this code consists of the Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA)-1 implementation and functionality for unsealing a key file used in Full Disk Encryption (FDE) with Linux Unified Key Setup (LUKS).

Given that the firmware source code is not publicly available, it is only possible to make limited assertions regarding the extent of its modifications. The BIOS provides three TPM functions to facilitate communication with the TPM. Furthermore, the firmware is responsible for measuring every software component to which it transfers control of the system.

Grub itself is significantly more complex, as demonstrated by the output of the cloc command shown in Listing 5. The large number of lines of code corresponds to the extensive set of features provided by Grub. Support for themes, modules, and internationalization—each loaded from the disk across a variety of file systems—complicates the task of making definitive statements regarding whether all files have been properly measured.

The same applies to BIOS firmware, which can be extended through so-called Option ROMs. An Option ROM is firmware that resides, for instance, on a PCI expansion card and is executed by the BIOS after the POST (Power-On Self-Test) process [46] (chap. 4-12).

In summary, the SRTM concept is straightforward in theory, but its secure implementation in practice is complicated by a flexible and modular boot process. However, even if the Chain of Trust does not cover everything, the difficulty of executing a successful attack increases with each measured component.

Functionality¶

To utilize TrustedGRUB2, the platform must meet the following criteria: the processor architecture must be either i386 or amd64, and the firmware must be a traditional BIOS or UEFI with CSM enabled. Additionally, a TPM is required within the system. If these prerequisites are fulfilled, TrustedGRUB2 and its provided functionalities can be employed [42].

TrustedGRUB2 establishes a foundation for runtime reporting by measuring system components during startup. This process enables functionalities such as granting access to corporate networks exclusively to authorized clients. The Chain of Trust constructed by TrustedGRUB2 reduces the likelihood of returning PCR values that do not correspond to the executed software, thereby enhancing the integrity of the verification process.

A particularly relevant feature for this work is the ability to decrypt a keyfile for an encrypted LUKS volume during startup through TPM unsealing. GRUB supports LUKS volumes and can decrypt them using the cryptomount command. TrustedGRUB2 extends this functionality by enabling the keyfile to be decrypted through TPM unsealing prior to use. This ensures that decryption, and consequently the system boot, can only proceed if the measured components remain unaltered. To enhance security, an SRK (Storage Root Key) should be set, ensuring that decryption cannot occur without the owner’s consent.

Usability¶

TrustedGRUB2 is not included in the official package repositories of Arch Linux, Ubuntu, or Fedora (as outlined in Listing 6). Consequently, utilizing this bootloader requires downloading the source code along with all dependencies and manually compiling it. This process is cumbersome and represents the first significant drawback in terms of user-friendliness.

Due to the abandoned state of the repository, it is necessary to apply several patches from upstream GRUB to enable compilation on a current system. This step merely brings the code to a compilable state without incorporating bug fixes or newly introduced features from upstream GRUB. For individuals without experience in software development, this requirement can be considered a significant barrier to using TrustedGRUB2.

A positive aspect worth highlighting is the transparent manner in which the

bootloader was extended. Users already familiar with GRUB will intuitively

understand how to work with TrustedGRUB2. The installation process is identical,

and there are no differences in the configuration file used for booting a Linux

kernel. Additionally, the newly introduced commands, such as measure and

readpcr, are both practical and straightforward to use via the GRUB command

line.

Unfortunately, a seal command for initially encrypting a keyfile is not

available, and attempts to execute the measure command were unsuccessful.

During testing, the command consistently failed with the error message:

TCG_HashLogExtendEvent failed: 0x10001.

The poor user-friendliness of TrustedGRUB2 makes a compositional solution unfeasible, as the effort required to bring this project up to date would be excessively high. However, its technical implementation is well-designed and can serve as an inspiration for developing a custom implementation.

1 $ git clone https://github.com/rhboot/grub2.git; cd grub2

2 $ git log --since 1.6.2017 --oneline --no-merges | wc -l

3 294

1 $ rg -il ')/\* BEGIN TCG EXTENSION \*/' | xargs sed -En \

2 '/\/\* begin tcg extension \*\//I,/\/\* end tcg extension \*\//Ip'

1 $ cd /TrustedGRUB2

2 $ cloc **/*.c **/*.h

3 1316 text files.

4 1301 unique files.

5 20 files ignored.

6

7 github.com/AlDanial/cloc v 1.84 T=2.28 s (571.3 files/s, 163019.2 lines/s)

8 -------------------------------------------------------------------------

9 Language files blank comment code

10 -------------------------------------------------------------------------

11 C 827 40065 32101 234678

12 C/C++ Header 474 8128 15644 40589

13 -------------------------------------------------------------------------

14 SUM: 1301 48193 47745 275267

15 -------------------------------------------------------------------------

16 $

1 $ # Fedora 31

2 $ dnf search trusted grub

3 Last expiration check: 0:03:51 ago on Fri 13 Dec 2019 05:37:18 AM EST

4 No matches found

5

6 $ # Ubuntu 19.10

7 $ apt-cache search trusted grub

8 $

Qubes AEM¶

This chapter examines QubesOS and its qubes-anti-evil-maid extension. Appendix A provides a detailed description of the setup process for this system. The analysis, similar to that of the other test system, explores the technical architecture and evaluates its functionality, complexity, and user-friendliness.

Technical details¶

Similar to the TrustedGRUB2-based system, the disk is partitioned utilizing the

partition table located in the Master Boot Record (MBR). As demonstrated by the

fdisk and lsblk outputs in Listing 7, the disk was

segmented during installation into an unencrypted boot partition and a

LUKS-encrypted partition. While the partitioning methodologies are consistent

across both systems, significant differences arise in the implementation of

their respective Roots of Trust for Measurement (RTM).

Qubes-AEM employs a Dynamic Root of Trust for Measurement (DRTM). However, during the boot process, a Static Root of Trust for Measurement (SRTM) chain is also initiated, which terminates at the Grub bootloader. Consequently, the upper portion of Fig. 10 is identical to that presented in the TrustedGRUB2 analysis in the Technical details.

Fig. 10 Qubes AEM boot chain¶

In this configuration, Grub does not directly boot the Linux kernel but instead loads the open-source software tboot to enable a measured and verified operating system start using Intel Trusted Execution Technology (Intel TXT) [43]. tboot prepares specific memory regions in accordance with the requirements of the GETSEC[SENTER] processor instruction and subsequently executes it.

The CPU microcode then initiates the processor preparation process. The Initiating Local Processor (ILP) sends a synchronization signal to all other cores and waits for their ready signal. Subsequently, the ILP loads the SINIT Authenticated Code Module (ACM) and verifies its signature. If the signature is valid and originates from Intel, the SINIT ACM is executed [38] (chap. 1.2.1).

Before the Measured Launch Environment (MLE)—in this case, again tboot—gains

control of the system, PCR-17 and PCR-18 are reset and then extended.

Intel categorizes the contents of PCRs into Details and Authorities. The actual

hash value of an entity, such as the SINIT Authenticated Code Module (ACM), is

classified as a Detail and extends PCR-17, while the hash value of the

public key used to verify the signature is categorized as an Authority, thereby

extending PCR-18.

If rollbacks do not present a security vulnerability, this separation allows a

secret to be sealed with PCR-18 and later unsealed, even after the

underlying code has been updated. A detailed list of which entities contribute

measurements to PCR-17 and PCR-18,, in addition to the SINIT ACM and the

MLE (tboot), can be found in the MLE Software Guide [38] (chap. 1.10.2).

The Measured Launch Environment (MLE), represented by tboot, assumes

responsibility for continuing the Chain of Trust. It extends the Platform

Configuration Registers (PCRs) as follows: PCR-17 is extended with the tboot

policy and the tboot policy control value. PCR-18 is extended with the hash

value of tboot itself and the first module specified in the grub.cfg

configuration file. In this instance, this module is the Xen Hypervisor. The

grub.cfg file, as shown in Listing A.6, specifies the Xen Hypervisor along with

additional modules. The hash values of these modules are sequentially appended

to PCR-19 in the order they are listed in the configuration file [43].

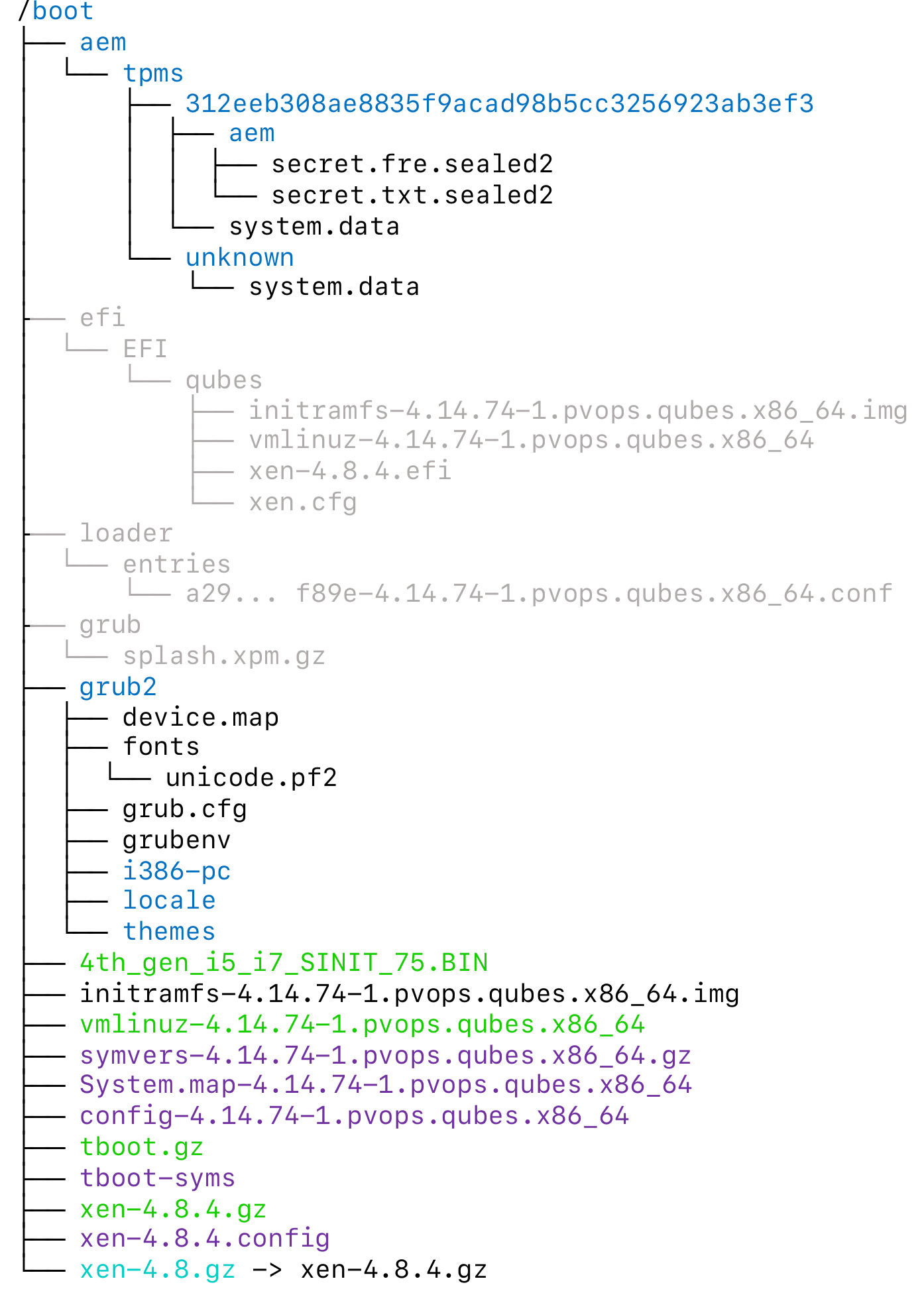

Fig. 11 Qubes AEM boot contents¶

Once control of the system is handed over to the Xen Hypervisor, the Measured Launch process for tboot is considered complete. However, Qubes-AEM extends beyond merely providing a measured launch with Dynamic Root of Trust for Measurement (DRTM). It also offers a comprehensive solution designed to detect and mitigate Evil Maid (EM) attacks.

Fig. 11 illustrates the contents of the unencrypted boot partition. For clarity and to conserve space, the components of the grub2 directory that were previously displayed Fig. 9 have been omitted.

While this system contains significantly more files than the one using TrustedGRUB2, the number of relevant files is comparable. The grayed-out files can be safely deleted without altering measurement values or affecting the boot process. Files highlighted in purple are informational only, typically containing symbols or copies of configuration files used during the compilation of the kernel or the hypervisor.

In addition to the Linux kernel and its associated initramfs, which were also present in the TrustedGRUB2 system, the Qubes-AEM setup includes the hypervisor, tboot, and the SINIT ACM. These components, integral to the system’s functionality, have been discussed in detail earlier.

The remaining files in the aem directory are created during the initial boot of Qubes OS with the AEM extension enabled. To fully understand their contents and purpose, it is necessary to first examine the functionality of the AEM extension in detail.

Fig. 12 Qubes AEM Login Post¶

During the first boot after installing the AEM software, the process deviates from a standard boot sequence. Initially, as in a regular setup, the user enters the password to decrypt the hard drive. Following this, the first major distinction becomes evident. Qubes-AEM begins the sealing process for the defined secrets, binding them to the contents of PCR 13, 17, 18, and 19.

PCR 13 is extended by Qubes-AEM with the LUKS header of the encrypted

partition, while the remaining PCR contents have already been discussed. Beyond

the user-created file secret.txt, Qubes-AEM attempts to seal additional

items:

Shared secret for a Time-Based One-Time Password Algorithm (T-OTP):

secret.otp.Keyfile for Full Disk Encryption (FDE):

secret.key.Freshness Token:

secret.fre.

These elements will be examined in detail in Section 3.2.3, which focuses on functionality. With the initial sealing process complete, the integrity of the system can be verified during subsequent boots, even before entering the FDE password.

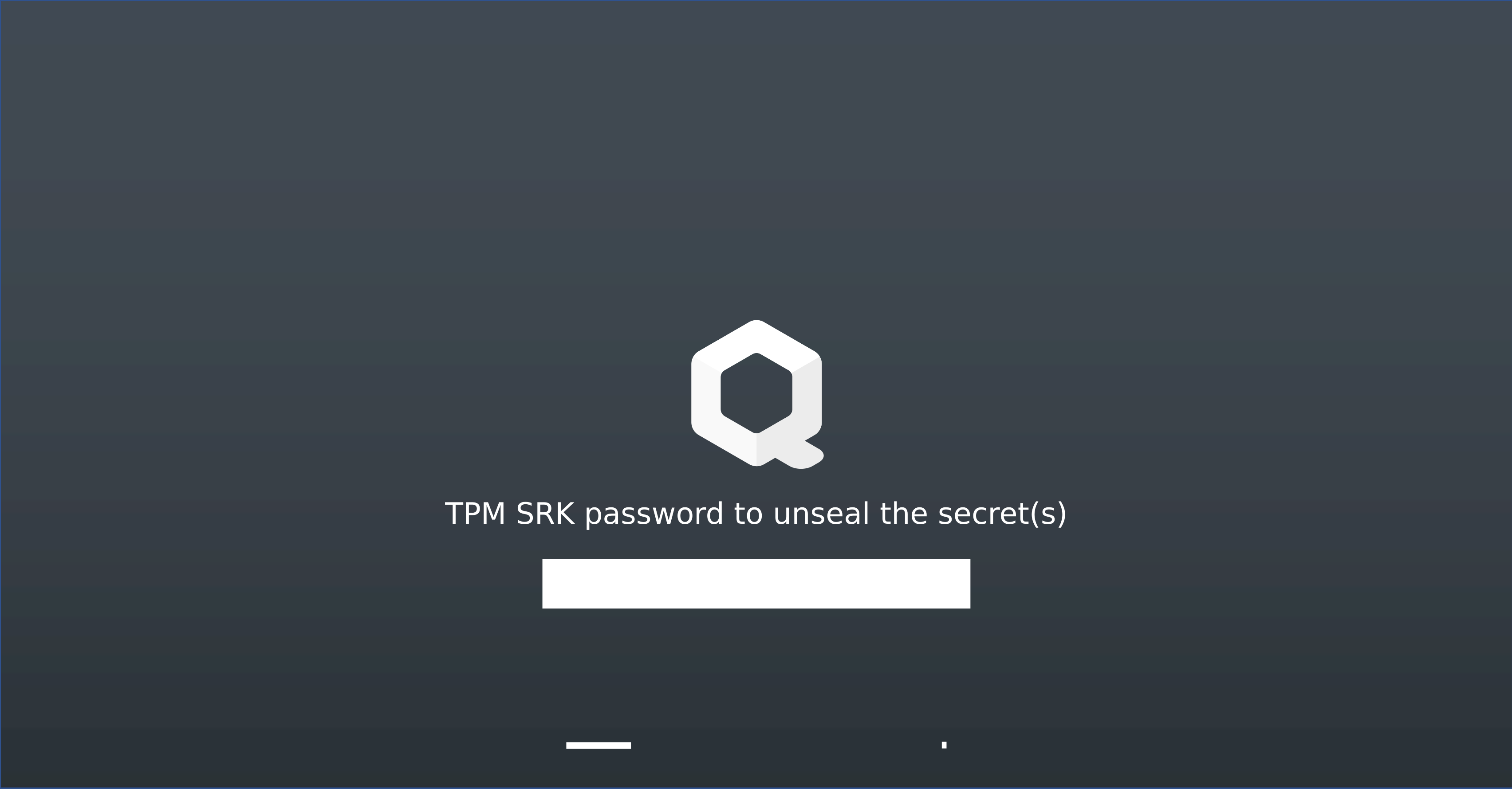

Fig. 13 Qubes AEM Login SRK¶

Immediately after startup, the system prompts for the SRK password. This step prevents unauthorized individuals from accessing the secret and using it to set up a compromised system. Such a manipulated system could, irrespective of the software being executed, display the secret without discrepancy. As a result, the victim would be unable to discern whether the system has been tampered with, thereby compromising the confidentiality of the FDE password.

Qubes-AEM also allows configuring a USB stick as a boot medium. In such a setup, the use of an SRK password becomes optional, offering a trade-off between usability and security. However, a TPM with an active SRK password provides an additional layer of protection and is therefore inherently more secure than a TPM without one. Following the password entry (if required), the unsealing process is initiated, and the secret is displayed.

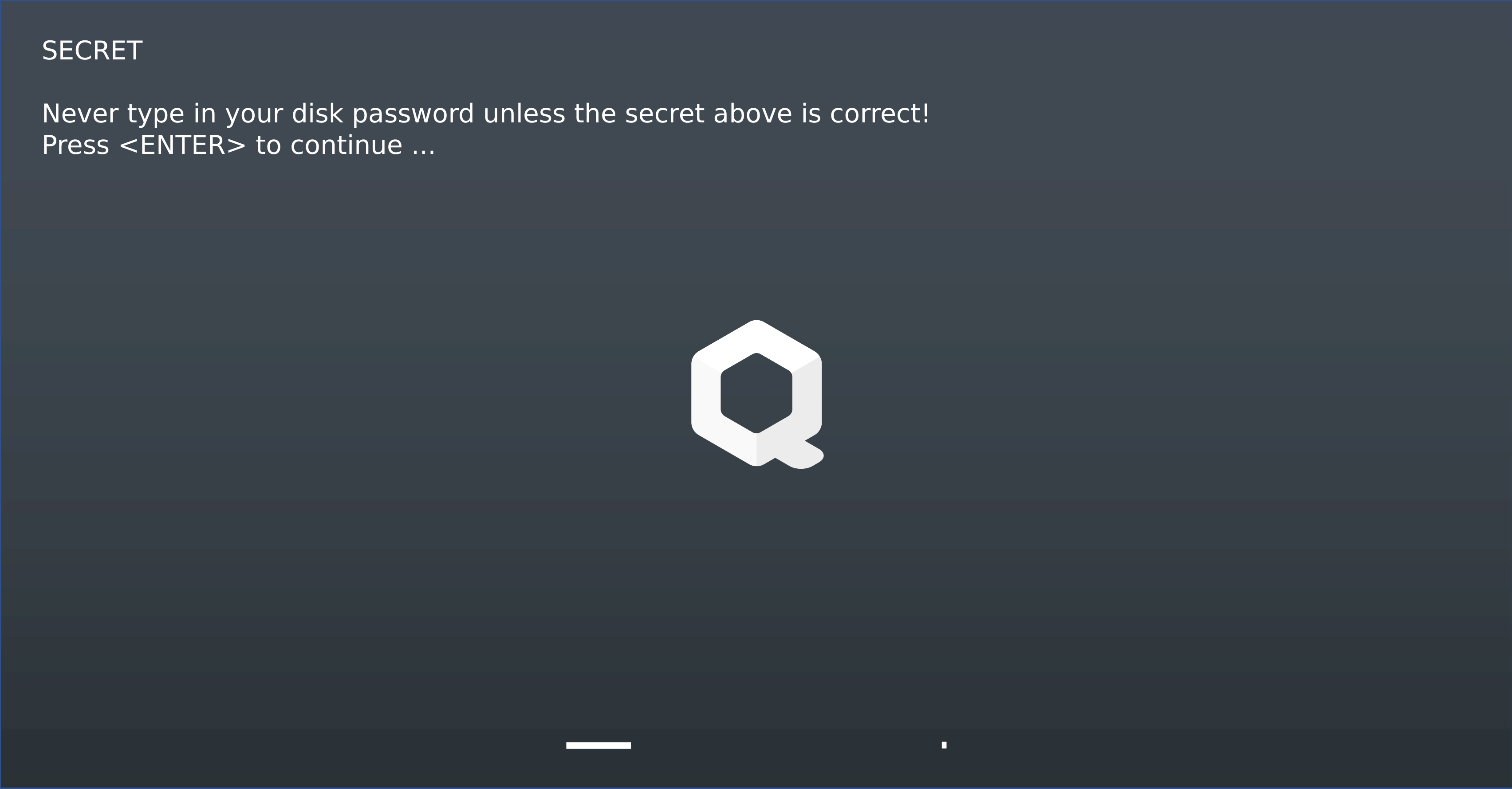

Fig. 14 Qubes AEM Login secret¶

Fig. 14 illustrates the Qubes-OS login screen presented after entering the SRK password. It displays the secret specified during installation, labeled SECRET, alongside a prompt advising that the FDE password should only be entered if the secret is verified as correct. Since the secret is known exclusively to the user, it can only be displayed if the TPM permits unsealing. This process occurs solely when the PCR values match those recorded during the sealing process. Maintaining these values requires the measured components, such as the Linux kernel or the hypervisor, to remain unaltered.

This demonstrates the concept of a platform-state-bound secret and underscores the critical role of safeguarding the secret in maintaining security. Without proper confidentiality of the secret, the system’s security is fundamentally compromised.

With this foundational understanding, we now turn to a more detailed examination of the technical implementation of Qubes-AEM. To achieve this, we first analyze the environment that is active at the time of login.

Before the actual root filesystem is mounted, the Linux kernel operates using the initramfs as its root filesystem. The initramfs is a Gzip-compressed Copy In, Copy Out (CPIO) archive containing only the programs and modules necessary for the kernel to mount the actual (encrypted) root filesystem [47]. The construction of this archive varies across different Linux distributions. Under Qubes OS, the tool dracut is employed for this purpose.

Qubes-AEM leverages dracut’s configuration options to incorporate specific scripts and programs into the initramfs, ensuring that the required functionality for its integrity verification processes is included [48].

Qubes-AEM is implemented entirely through configuration files and sh or bash scripts. Consequently, it has numerous dependencies, including a complete TPM software stack, the tpm-tools, three small utilities developed specifically for Qubes OS, and various standard Linux utilities such as file and grep [48] (module-setup.sh).

These scripts operate in two distinct environments: the initramfs and the decrypted root filesystem. They manage interactions with the TPM and the Plymouth login screen, enabling users to detect potential Evil Maid Attacks (EMAs) effectively.

This chapter has covered a wide range of topics, starting with a system leveraging a Dynamic Root of Trust for Measurement (DRTM), followed by the Chain of Trust established by Qubes OS with the AEM extension, and concluding with the initramfs phase of a Linux system and the technical specifics of the Qubes-AEM software.

Complexity¶

For a meaningful comparison, we begin by examining the size of the software components. At the start of the Chain of Trust, the SINIT ACM module is executed. Since its source code is not publicly available, it is not possible to provide an assessment of its size. Following this, tboot is executed, with its line count as determined by cloc shown in Listing 8. This reveals that tboot alone comprises over 20,000 lines of C/C++ code. In contrast, the size of Qubes-AEM is significantly smaller, consisting of approximately 900 lines of script code (see Listing 9).

Dynamic Root of Trust for Measurement (DRTM) offers the advantage of a shorter Chain of Trust compared to a comparable system using Static Root of Trust for Measurement (SRTM). A shorter chain is generally easier to comprehend and less complex. However, this simplicity comes with the drawback that the platform must be trusted to a greater extent than with SRTM.

For example, DRTM introduces resettable Platform Configuration Registers (PCRs). This operation requires a specific privilege level, referred to as Locality, which is controlled by the platform. If there are vulnerabilities in the implementation, the locality may be spoofed, potentially allowing the modification of PCR contents.

Shell scripts are widely understood by developers and system administrators, as they are commonly used to automate workflows. Combined with their relatively small size, this makes them the component with the lowest complexity in the system. However, these scripts include features that increase complexity without necessarily enhancing security.

One such example is the capability to boot multiple Qubes-OS devices from a single USB stick. While this functionality adds flexibility, it does not contribute directly to the system’s security posture.

DRTM reduces the Chain of Trust at the cost of increasing the overall system complexity. The CPU must meet specific requirements, making the solution ultimately tied to a particular platform. While both AMD and Intel offer these extensions, tboot currently supports only Intel. The numerous features and the DRTM approach contribute to a relatively high level of complexity.

Functionality¶

To leverage the full functionality of Qubes-AEM, the system must meet all prerequisites specified for the TrustedGRUB2 system. Additionally, the processor must be an Intel model equipped with the Intel Trusted Execution Technology (TXT) extension. Once these requirements are satisfied, the software can operate with its complete feature set, delivering its intended capabilities [43] [44].

Qubes-AEM leverages Intel TXT to establish a Chain of Trust with a dynamic root. The resulting PCR values can be utilized at runtime to verify that the system was booted with a specific configuration. QubesOS enables this functionality by providing a complete TPM software stack for runtime queries, ensuring seamless interaction and verification.

The Qubes-AEM extension utilizes PCR values to detect software manipulations. The fundamental mechanism was discussed in Technical details, where the focus was on a configuration without an external boot medium and with an SRK password set. Qubes-AEM provides several configuration options, which are detailed in the following sections.

In addition to the internal boot medium, a USB stick or an SD card can be used as an external medium. In this configuration, the bootloader and all unencrypted data reside on the external medium, which, due to its small size, can be easily secured. In its simplest use case, the external medium serves the same purpose as the SRK password in an internal installation—protecting the secret. An attacker would need simultaneous physical access to both the PC and the boot medium to access the secret [44].

To safeguard the confidentiality of the password and secret against video surveillance or shoulder surfing, Qubes-AEM offers multifactor authentication. During the creation of the external boot medium, a shared secret is generated and can be imported into an app like “Authy,” “Google Authenticator,” or “FreeOTP” either via a barcode or manual input. Instead of displaying a static secret during login, a one-time password (OTP) is shown as a six-digit number, which must match the number displayed in the app.

To avoid entering the FDE password, Qubes-AEM generates a keyfile that can also decrypt the full disk encryption (FDE). This keyfile is secured with a separate, unique password. After entering the required information, the system boots, ensuring that even if someone records the input and output during the startup process, they gain no knowledge of either the secret or the FDE password.

The Freshness Token, briefly mentioned during the examination of the boot partition contents, plays a critical role in the system’s security mechanism. Essentially, it consists of 20 bytes of random data that, like the secret, are sealed by the TPM. Upon successful system authentication, the hash of the Freshness Token is stored in the Non-Volatile Random Access Memory (NVRAM) of the TPM.

During the next boot, the system verifies whether the token’s hash matches the value stored in the NVRAM and displays an alert if there is a mismatch. After successful authentication, a new Freshness Token is generated for subsequent boots. This mechanism ensures that attackers with access to a copy of the external boot medium must start the laptop before the rightful owner has a chance to do so. Otherwise, the Freshness Token is regenerated, invalidating the old one.

This feature provides protection for the shared secret used in the Time-Based One-Time Password (T-OTP) system. If an invalid Freshness Token is detected, Qubes-AEM halts the process, safeguarding the system against unauthorized access. In the event that a boot medium is lost, Freshness Tokens can also be manually invalidated [61].

A unique ID stored in the NVRAM of the TPM enables the use of a single USB stick as an external boot medium for multiple QubesOS instances. However, to achieve the highest level of security, it is recommended to use a separate boot medium for each device. Furthermore, these media should be stored securely and separately to minimize the risk of unauthorized access or compromise.

Usability¶

As with most software aiming for the highest level of security, user-friendliness is not a strong point. This challenge begins with the QubesOS operating system itself, which is not compatible with all hardware configurations. During the course of this work, attempts to run QubesOS on a Dell XPS 15 9550 and a ThinkPad T410 were unsuccessful, despite both devices being listed in the Hardware Compatibility List (HCL) and having been successfully tested with older versions of QubesOS by other users.

The AEM extension also has its weaknesses in terms of user-friendliness. While the installation of the required components is relatively straightforward, setting up a system with AEM protection is complex. It involves several non-sequential steps, and certain technical details, such as manually downloading the correct SINIT ACM, must be addressed independently. For a successful installation, the accompanying README file must be meticulously followed step by step. Even with strict adherence, there is still a risk that the system may not function correctly due to unforeseen issues or subtle configuration errors.

The first error encountered during this work was that the GRUB configuration file did not set the SINIT ACM as a module after installation. Although this issue was fixed in the repository back in September 2017, a new version with the fix did not appear in the package repositories until February 12, 2018 [45]. Without the SINIT ACM set as a module, the Chain of Trust cannot be established, rendering Qubes-AEM nonfunctional.

Another issue with lesser impact is the invalid token in the barcode when using multifactor authentication. The URL embedded in the barcode contains a line break at the end, which is the reason why importing it into “Authy” fails.

In addition to the two previously mentioned issues, the operating system with an AEM configuration only starts after an additional setting for the hypervisor has been made in the grub.cfg file. The tboot README [43] contains an example configuration where this setting is applied. Therefore, it is likely that the configuration created by Qubes-AEM is faulty.

A positive aspect is the seamless integration into the login process. Once the system is correctly set up, no further intervention is required. Before the text box for entering the FDE password appears, Qubes-AEM displays the secret.

1 $ fdisk -l /dev/sda

2 Disk /dev/sda: 476.96 GiB, 512110190592 bytes, 1000215216 sectors

3 Disk model: SAMSUNG MZ7TE512

4 Units: sectors of 1 * 512 = 512 bytes

5 Sector size (logical/physical): 512 bytes / 512 bytes

6 I/O size (minimum/optimal): 512 bytes / 512 bytes

7 Disklabel type: dos

8 Disk identifier: 0xa8b6ae5b

9

10 Device Boot Start End Sectors Size Id Type

11 /dev/sda1 * 2048 2099199 2097152 1G 83 Linux

12 /dev/sda2 2099200 1000214527 998115328 476G 83 Linux

13

14 $ lsblk -f /dev/sda

15 NAME FSTYPE LABEL UUID

16 sda

17 sda1 ext4 aem ccc1704b-607b-4417-b60e-c3bba2e0224d

18 sda2 crypto_LUKS e2e988a9-c19b-4af8-b9b5-5d4efd6beef6

1 $ cd /tboot-1.9.10/tboot

2 $ cloc ./**/*

3 89 text files.

4 89 unique files.

5 1 file ignored.

6

7 github.com/AlDanial/cloc v 1.84 T=0.32 s (273.3 files/s, 103615.1 lines/s)

8 --------------------------------------------------------------------------

9 Language files blank comment code

10 --------------------------------------------------------------------------

11 C 41 3207 3882 16988

12 C/C++ Header 39 946 2185 4691

13 Bourne Shell 2 39 54 422

14 Assembly 4 103 276 379

15 make 2 47 39 102

16 --------------------------------------------------------------------------

17 SUM: 88 4342 6436 22582

18 --------------------------------------------------------------------------

19 $

1 $ cd /qubes-antievilmaid

2 $ cloc ./**/*

3 23 text files.

4 19 unique files.

5 14 files ignored.

6

7 github.com/AlDanial/cloc v 1.84 T=0.06 s (150.2 files/s, 30166.4 lines/s)

8 --------------------------------------------------------------------------

9 Language files blank comment code

10 --------------------------------------------------------------------------

11 Bourne Shell 3 135 48 563

12 HTML 1 20 0 518

13 Bourne Again Shell 4 120 47 353

14 Ruby 1 0 0 3

15 --------------------------------------------------------------------------

16 SUM: 9 275 95 1437

17 --------------------------------------------------------------------------

18 $

Conclusion¶

With the completion of the analysis of QubesOS-AEM, two systems with different approaches now exist, which will be compared in the following.

Both systems use different approaches for the Root of Trust for Measurement. TrustedGRUB2 utilizes SRTM, which, compared to the DRTM used in Qubes-AEM, performs better. The following arguments support this statement:

The theoretical concept behind SRTM is simpler to understand compared to DRTM. In the case of an immutable CRTM, the execution begins, and all software components are measured by their predecessor. DRTM, on the other hand, involves resettable PCRs and privilege levels (Localities) that are enforced by hardware, and to verify these, knowledge of a closed-source Intel CPU is required.

Specifically for Intel’s implementation, DRTM utilizes the SINIT ACM (Intel-signed closed-source software). Obtaining this binary alone is cumbersome. Furthermore, several security vulnerabilities have already been discovered in older versions [49], [50].

The required code for SRTM is significantly smaller than that for DRTM. This makes it easier to understand and implement independently.

The features offered by Qubes-AEM are significantly more comprehensive than those of the TrustedGRUB2 system. While TrustedGRUB2, with a set SRK and a LUKS keyfile sealed with the TPM, can detect a subset of EM attacks, external storage devices, multifactor secrets, and DRTM are exclusive to Qubes-AEM and bring the security up to a different level.

In terms of user-friendliness, both systems perform similarly poorly. The biggest issue with TrustedGRUB2 is its neglected state, while for Qubes-AEM, the complex setup process and the errors that occur during a typical installation are the main challenges.

Qubes-AEM is much better maintained. The pull request submitted for this work was merged within a day, and since the start of this research, another release of the extension has been published. In contrast, TrustedGRUB2 has not received any commits since 2017, and pending pull requests are not being integrated. Qubes-AEM also benefits from being designed for an operating system where this feature holds significant importance (with its own TPM entry in the HCL [62] and documentation found under Security in the Qubes documentation [63]), which ensures that it is well integrated.

This paragraph concludes the state-of-the-art analysis, in which two different systems with countermeasures against EM attacks were presented and analyzed. The foundational knowledge gained so far has been supplemented with two practical implementations. Using this information, different solution approaches will be presented in the next chapter, one of which will ultimately be implemented.